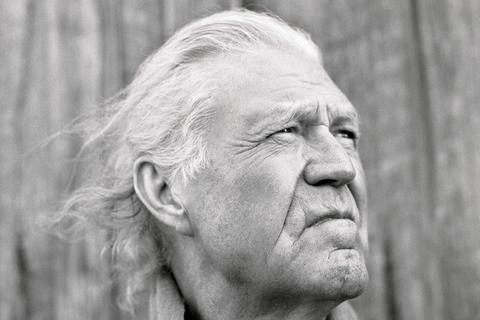

Billy Joe Shaver

I was not even born yet when my father first tried to kill me.

It was June and the evening light had started to fade, but it was still hotter than nine kinds of hell. We were outside of Corsicana, a little cotton town in northeast Texas, and I was in my mother's belly, two months from entering the world.

Buddy Shaver was convinced that my mother, Victory, was cheating on him. That was bullshit, and he probably knew it. But he'd been drinking. My father was half-French, half-Blackfoot Sioux, and one-hundred-percent mean. He drank a lot, and the booze didn't mix well with his Indian blood. You know there are some guys who are just born naturally strong, with big shoulders and a chiseled upper body even though they never work a lick at it? That was my father, and my mother didn't have a chance.

It's just a story I've heard, told by family members who don't enjoy the retelling. But I can see it as clearly as if I was there. They were standing next to a small stock tank with black, still water. It was the middle of nowhere, with no roads or houses in sight. Who knows what he told her to get her out there, or whether she knew what was coming when they stopped there? He held nothing back, yet his cold gray eyes showed no emotion as he beat her within an inch of her life. When she was down, he stomped her with his cowboy boots until she stopped struggling. Then he tossed her limp body into the water like a sack of potatoes. Years later, when I was a grown man, my momma couldn't stand to be around me when I wore cowboy boots—she never could forget what they did to her that night.

Momma laid there for hours until an old Mexican man showed up to water his cattle. Even though he knew my kinfolk pretty well, he didn't recognize her at first. He thought she was dead. But she spoke to him through the bruises and the blood, and he threw her over the back of his horse and carried her home.

The violence of that night set the stage for my childhood: It's the reason my father left, it's the reason my mother didn't want me, and it's the reason I went to live with my loving grandmother. In many ways, I think that night is the reason I write country songs.

When you get right down to it, country music is essentially the blues, and that night introduced me to the blues. In the years since then, they've never left me. I've lost parts of three fingers, broke my back, suffered a heart attack and a quadruple bypass, had a steel plate put in my neck and 136 stitches in my head, fought drugs and booze, spent the money I had, and buried my wife, son, and mother in the span of one year.

But I'm not here to complain or ask for pity. Life is hard for everybody, just in different ways. I'm not proud of my misfortune—I'm proud of my survival. For years, my family kept a bundle of life insurance on me because they were sure I would be the first to go. But as I write this, at sixty-four years of age, I'm still here and they are all gone.

The question is—why? That's something I've been thinking about a lot lately.

Throughout my career as a songwriter, I've just written songs about me—the good and the bad, the funny and the sad. I've written songs about other people, but I don't sing other people's songs. They're just little poems about my life, and I've never pretended they were anything more. Despite all my ups and downs, I've never been to therapy or rehab or any of that stuff. The songs are my therapy.

But after my shows, people always come up to me and thank me for writing those songs. They tell me about their lives, and how a song of mine helped them through a tough patch or made them smile during a difficult time. Sometimes they say I inspired them—that if I can make it through my life, they can damn sure get through theirs. When we're done talking, I give them a hug and tell them I love them. I know exactly where they are coming from.

My point is, it's truly a miracle I survived that night by that stock tank, and I don't mean that the way most people say it—like it's a lucky break. I think God allowed me to live. He wanted me to tell my story.