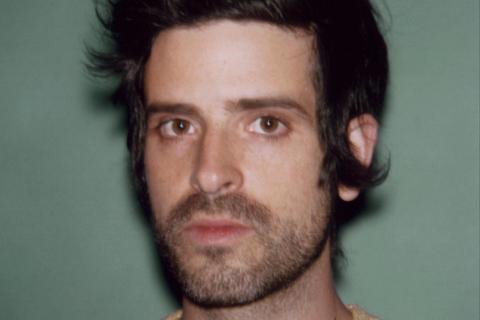

Devendra Banhart

For his Nonesuch debut, Devendra Banhart chose the title Mala, literally the Serbian word for “small,” but used colloquially in Eastern Europe as a term of endearment—“like sweetie pie,” Banhart explains. It was a placeholder during most of the recording, a working title offhandedly inspired by a ring his fiancée, the Serbian photographer and artist Ana Kras, had given him with that word on it. But the name stuck, and it proves to an apt one for an album so intimate in scale and open of heart.

Banhart’s previous effort, 2009’s What Will We Be, took him to Northern California where he cut the disc accompanied by a full band and producer Paul Butler behind the board. Conversely, Mala, his eighth studio album, took shape back in his own “tiny, tiny home” in Los Angeles, where Banhart until recently resided. He and longtime cohort Noah Georgeson produced it together, playing most of the instruments themselves, using borrowed equipment and a vintage Tascam recorder they’d found in a pawn shop. The Tascam is a couple of decades’ old piece of gear “that a lot of early hip-hop had been made on,” says Banhart. “And knowing my songs are not hip-hop whatsoever, we thought it would be interesting to see how these kinds of songs would sound on equipment that was used to record our favorite rap. Let’s see how this technology would work for us.” It was a new approach for the pair. “In the past we were more like, let’s use the oldest equipment we could find.” The arrangements, beguiling yet relatively unadorned, harken back to Banhart’s earliest recordings, the do-it-yourself tracks that first garnered him acclaim a decade ago. The songs themselves, though, are less fractured fairy tales than real or artfully imagined depictions of the vicissitudes of romance, even if Banhart does lace his often seductive delivery with liberal doses of surreal humor.

These days Banhart appears more suave than shamanistic, though his gently delivered words still have an incantatory quality. His trademark falsetto warble is often supplanted by a lower-registered croon, especially when he vocalizes in Spanish on a track like “Mi Negrita”—a song he conjured up while envisioning himself “in an oversized suit, slightly sweaty” on the set of the Venezuelan variety show Super Sabado Sensacional, a program he’d watch as a child growing up in Caracas in the ’80s.

“In Spanish, I can have a lot more flexibility,” Banhart admits. “I have a limited vocabulary—in English and in Spanish—but with Spanish I can get more into the sound of the words, I can have more fun with it. I can even get more autobiographical in Spanish. I feel comfortable revealing more, expressing something sincere about trauma or pain, which is not really a space I’m comfortable occupying. I can take things further in Spanish.”

Speaking of his native tongue, Banhart acknowledges that “mala” in Spanish is the feminine form of “bad,” and, given the more outré, gender-bending garb he donned earlier in his career—featured most notoriously in a fashion spread for the New York Times’ T style magazine—he jokes, “I could be that bad female.”

A hint of darkness does exist around the periphery of Mala, bracketing the album, in fact. The opening cut, “Golden Girls” is downbeat and bass-heavy, evoking a young man isolated on a dance floor. Closing number “Taurabolium”—named after the altar/structure from ancient pagan ritual upon which a bull was slain, its blood pouring onto a white-robed priest below—is basically a syncopated chant: “I can’t keep myself from evil.” Banhart was thinking West Side Story when he arranged the tune, its finger-snapping rhythm coming from “a switchblade, a chain, a whip, and a box full of glass that we just stomped on.”

Mostly, though, the mood is lighthearted, mischievous, and, on a reverie like “Daniel,” pleasantly nostalgic. On “Für Hildegard von Bingen,” he casts a contemporary life for the 12th-century Catholic mystic and composer: “In my head there was this little movie, an alternative universe, I guess—Hildegard is sequestered in her cloister, and one day she gets a VHS cassette and it’s the prime era of the MTV VJ, and she just goes wild. ‘That’s it for me,’ she says. ‘That’s how I’m going to get my message across.’ So she escapes the cloister…and becomes a VJ.” On “Fine Petting Duck,” he duets with his fiancée Kras or, more precisely, duels with her as they portray ex-lovers with very different perspectives on their relationship. She wants to get back with him; he reminds her, in their wry call-and-response, what a thoughtless boyfriend he actually was. (And somewhere along the way, Banhart and

Kras switch—inscrutably, amusingly—from English to German as the arrangement morphs from a ’50s-tinged R&B/Doo-wop/Mickey and Silvia-type vibe to a Teutonic house beat.) The anti-romantic banter is more playful, even more honest, than your average love song; Banhart admits, “It’s so hard for me to write a sincere love song. It s got to be about what a piece-of-shit relationship we’re in now, always, somehow. But there are some sincere things here obviously—they’re all sincere, really, but you have to keep a sense of humor about it.”

Banhart emerged seemingly out of nowhere in 2002 with his first CD collection, Oh Me Oh My…The Way the Day Goes By the Sun Is Setting Dogs Are Dreaming Lovesongs of the Christmas Spirit, compiled by Swans frontman Michael Gira for his Young God label from homemade recordings the itinerant Banhart had amassed as he traveled the world. He was born Devendra Obi Banhart in Houston, Texas, but spent his childhood in Caracas, Venezuela; as a teenager, his family returned to the States, relocating in Southern California, where he soon became enamored of skateboard culture. “Ballad of Keenan Milton,” in fact, is an homage to the legendary skateboarder, who died tragically in 2001 in a freak accident.

Music was always a passion for Banhart, and he discovered it in ways both magical and haphazard. As a boy in Caracas, says Banhart,” I was surrounded by salsa, merengue, cumbia, some bossa nova—that was ubiquitous, you’d hear it on any street. But oh my God, at home we had Guns N’ Roses’ Appetite for Destruction and the Rolling Stones’ Hot Licks. I don’t know what these things are, I don’t know who these artists are, I’m just eight years old, but I know I want to do that, I want to sing like these people.” In what could be an excerpt from a David Sedaris monologue, Banhart claims he found his own voice one day when he was home alone and impetuously donned one of his mother’s dresses, grabbed her hair brush and started to sing. What came out—wobbly, high-pitched—didn’t resemble Axl Rose or Mick Jagger, but it was a prepubescent sound he could call his own, a touchstone, something that echoed, years later, in the falsetto of his early albums. In high school, Banhart became obsessed with rocksteady, bluebeat, and ska, which he’d learned about via skateboarding videos.

Finishing high school, he thought he would pursue a visual arts career so he enrolled at the San Francisco Art Institute, but he soon dropped out in favor of exploring music. He has, however, successfully maintained a parallel career as a painter: Banhart’s distinctive, minutely inked, often enigmatic drawings have appeared in galleries all over the world, including the Art Basel Contemporary Art Fair in Miami; the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels; and Los Angeles’ Museum of Contemporary Art. He has created the cover art for most of his records, including Mala, and in 2010 his artwork and packaging for What Will We Be was nominated for a Grammy.

San Francisco had an indelible influence on Banhart; the flamboyant dressing he adopted that entranced the fashion crowd (and fueled the “freak folk” and “New Weird America” labels the press attached to him) was inspired in part by the seriously subversive cross-dressing culture of San Francisco’s legendary performance troupe the Cockettes.

Like Nonesuch label-mates Caetano Veloso and David Byrne, with whom he shared a stage at Carnegie Hall, Banhart has embraced an astonishingly wide range of musical ideas, from folk to blues to the avant garde. He extols the late Arthur Russell, a relentlessly eclectic artist who was impossible to pigeonhole in his brief lifetime, and Banhart has brought back into the spotlight forgotten artists like late-’60s singer Vashti Bunyan, whose psychedelic folk he championed. He has collaborated with Brazilian legends Os Mutantes, the Swans, Antony and the Johnsons, and Beck, among others, and has engaged in art projects like conceptualist Doug Aitken’s monumental 2012 Song 1 video installation on the façade of the Hirschhorn Museum in Washington, DC.

For Banhart, his career remains “an adventure and an exploration.” Mala reveals a natural maturation of his style, especially as a singer. Banhart admits, “I don’t really take care of my voice, but, just like with playing guitar, you get more familiar with it, and you get better at it. I’ve always said that I’m very good at not knowing how to play the guitar but, really, it’s just that I’m very comfortable with the utter uncertainty of my approach.”